This Isn’t Delivery Work — It’s a Test of Patience

This Isn’t Delivery Work — It’s a Test of Patience

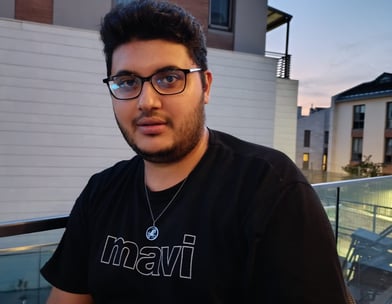

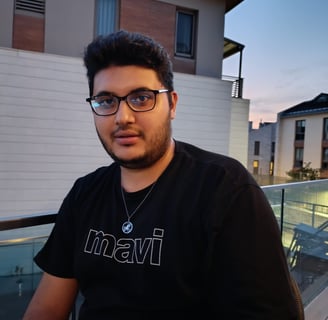

27-year-old Yunus Can Çelik graduated from Beykent University’s Business Administration department in 2020. However, his university diploma did not land him an office job — instead, it led him to a life spent on the streets, behind the wheel, and up and down apartment staircases. For the past five years, Çelik has been working in the cargo industry, both as a driver and a deliveryman. He started this job using his own vehicle — a choice that brought both benefits and challenges.For him, the greatest advantage is not being tied to fixed working hours. He starts at 8:00 a.m. and finishes according to the number of parcels — sometimes by 1:00 p.m., sometimes by 5:00 p.m. This flexible schedule gives him room to breathe. He says he earns well and therefore enjoys the job. “Right now, I need to save money, and this is the fastest sector to earn,” he explains. Çelik does not recommend this job for university graduates. However, he does suggest it to those who want to make money quickly without working long hours. What motivates him most is the high income and the relatively shorter working hours.

But the downsides are plenty. Using his own vehicle means that it wears out over time, losing value. Being stuck in traffic for hours is exhausting. Constantly dealing with people — including many unpleasant ones — adds to the stress. Still, he notes that there are good people too, even those who tip generously. Weather plays a big role in his daily struggles. In summer, waiting inside the hot vehicle becomes unbearable. He says this period wears him out physically. Winter and rainy days bring their own challenges. Taking leave is nearly impossible in this sector; workers are expected to be on duty almost all the time.

Some of the most physically demanding moments come when buildings lack elevators, or when elevators are broken. In such cases, he must climb multiple floors with heavy parcels. He mentions that his body is wearing down and that the job becomes almost impossible after a certain age. He shares a specific incident: he went to deliver a parcel to the 11th floor of a building, but the elevator was broken. He requested to leave the package in the mailbox, but the customer insisted it be brought upstairs. When he refused, saying it was not feasible, the customer replied: “It’s your job. Even if it’s 20 floors, you must bring it up.” Eventually, they reached an agreement — the customer agreed to come down, and the parcel was left in the vehicle. Çelik reflects on the situation by saying, “If you were going to come down anyway, why treat us like slaves?”

He states that many people around him look down on his job and often treat him harshly. “People see us like slaves,” he says. But despite all these difficulties, he continues working. His current goal is to save money — maybe one day, to step away from the driver’s seat and move toward a calmer life.

He said that it is not clear how much he earns but that he generally earns 2 minimum wages. It varies according to the number of packages and the distance of the customer. He said that the remaining amount is clear after deducting the fuel spent. He stated that his salary increases in the months when there are special days.

One morning, Yunus Can Çelik was leaving an apartment building when he accidentally hit his head hard on a glass door. The impact caused a cut on his forehead, and he immediately went to the hospital. Although his condition wasn’t serious, he was in pain and naturally assumed he wouldn’t be able to continue working that day. He called the cargo company to report the incident, expecting a simple “get well soon.” But the response he received left him stunned: “You seem able to work after hospital delivery — just keep going.”He says he was so shocked that he couldn’t even respond. “I couldn’t react — I just stayed silent,” he recalls. In that moment, he realized how little room there was for being seen as a human in this job. A worker with a head injury wasn’t even given the right to rest — a clear sign of the brutal system he’s part of.Çelik shares that it’s not only his employer who shows this lack of empathy. Sometimes, customers also display a similar attitude. He says that even after finishing work and going home, people call him saying, “I’m home now, bring my package.” When he explains he’s no longer on duty, some customers get angry and insist, “You’re supposed to deliver my package.”Through these words, he reveals how emotionally draining cargo delivery can be — not just physically exhausting, but mentally and emotionally wearing as well.